Chapel talk delivered on Tuesday, Dec. 9, 2025, in the Chapel of St. Peter and St. Paul by Art Teacher Brian Schroyer P’22

Opportunity is missed by most people because it is dressed in overalls and looks like work.” — Thomas Edison

When I was younger, I used to worry about making the wrong mark on a drawing. The blank page felt like a test I might fail — and of course I did fail all the time, in slow, loud and colorful ways. And each and every “failure” taught me something important about how to draw better the next time.

Today I want to give you a different perspective about mistakes. Don’t pretend mistakes aren’t real. Use them. Make them part of the picture. Mistakes are not the opposite of art — they are one of art’s raw materials.

This idea matters because it works for more than just making marks on paper. You make choices, you start projects, you say things, you navigate friendships, you apply for summer jobs — and sometimes those moves feel wrong. What if we stopped treating those moments as evidence of who we are, and started treating them as information we can use?

Let me explain, and I want to give you three practical things to carry with you after you walk out of this room.

One: A mistake tells you one thing — you learned something you didn’t know before. Imagine you’re halfway through a painting and you smear the edge with your sleeve. Or you spill something on it. Or the easel wasn’t secured properly and you’re just walking past it and the wind of your passage is enough to make it fall face-down on the floor. I mean I’ve never done those things, but I know a guy…

Your instinct might be to panic and try to hastily cover it up or undo it. The better move — artistically and emotionally — is to ask, “What did this reveal?” Maybe it added a texture you didn’t plan for. Maybe it connected two areas that felt too separate. Maybe it suddenly made the picture look more alive. Maybe it really IS a mess now.

In my studio, students sometimes come up to me and whisper, “This project isn’t going well. Please help.” One of my first questions is often: “What did you just try?” Most of the time they haven’t tried anything in a while because they’re waiting to get it right on the first go. But the moment they actually try something — even if it looks wrong — there’s suddenly evidence to use: value and color choices, composition problems, things that need more contrast, things that might be worth keeping.

So step one when a project feels ruined: notice. Don’t erase the mistake right away. Pause, look, and name what’s changed. That’s data. Treat your mistake like a clue in a mystery, not a verdict that you are bad at something.

Two: A mistake can open new directions you couldn’t imagine. When you make a mark that feels wrong, it can force the work to change course — and that’s often where originality lives. Some of the most interesting work I’ve seen started with a “wrong” decision that became the engine of the piece.

We don’t have time for me to thrill you with a couple thousand years of art history but think about those times a song found its groove because a musician hit a rhythm that didn’t fit the original plan, or a writer found the voice mid-sentence because a paragraph “failed.” In those moments the artist didn’t go back to the safe plan. They leaned into the surprise and asked: “Where can this go?”

In 1968, Dr. Spencer Silver was working on a super-strong adhesive to be used in the aerospace industry and he failed. His work yielded a low-tack, pressure sensitive adhesive that stuck to surfaces and then peeled off without leaving marks. He was shooting for the moon and he landed on your desk by inventing Post-it notes. By mistake.

You can do the same thing with your life. If a meeting doesn’t go as you expected, if your essay takes a bad paragraph, if a relationship goes sideways — sometimes the best response is not to rewind but to ask, “Okay, given this, what new thing can I try?” The failure points you to possibilities you didn’t have before.

So the next step is experiment. Try one small, deliberate change that leans into the mistake. If your drawing lost contrast, add a heavier line. If your audition was shaky, audition again but try a different approach. If a friendship fizzled, try a different kind of conversation. Mistakes are forks in the road, not dead ends.

Three: Build a revision plan — simple steps you can actually use. Now that we’ve invited all these mistakes into our lives, we need to have a practical approach ready, a plan! Artists revise constantly. We don’t trash the canvas and walk away (usually). We make a plan and we iterate. You can make a tiny revision plan for anything that goes wrong. Here’s a three-step plan I have asked students to try, and it works for projects, friendships, and college essays too.

Step one: Observe — name what happened. Be specific.

“I lost my shading”

“I forgot my evidence”

“I interrupted them”

“I do not like spicy things and put way too much hot honey on that,”

Naming helps you stop spinning and start solving. Charles Kettering said, “a problem well defined is a problem half-solved,” and that guy had 186 patents, and he is the reason you don’t have to crank on a handle to start your car.

Step two: Change one thing — pick one small move that might help. Don’t try to fix the whole mess. Small moves are less scary and more testable. Picture a video game boss fight where you keep losing. You could rage-quit, or throw the controller… or you could try changing just one variable. Switch out the heavy sword for the fast dagger. Focus on dodging and movement instead of blocking. You cannot rewrite the game code, but you can try out different solutions.

Step three: Reflect briefly. After the change, step back and ask, “Did that help? What else do I now know?” So you changed your approach to the boss fight and you still died. But you survived 10 seconds longer than last time. That’s not failure, that’s data. Now you’re not just guessing, you’re testing, experimenting, and refining.

If you do those three things — observe, change one thing, reflect — you’ll be surprised how quickly messy-looking work becomes interesting work.

Now, I know there’s a pressure in our culture to make everything perfect the first time. Social media makes it worse: people publish highlights, and we assume everyone else gets it right. But the truth is the opposite. The people who seem to have it together are usually the ones who have practiced revision and tried many wrong things. They’ve learned to make mistakes into materials.

Here’s what I want you to try this week. I want to encourage you to intentionally do one small, slightly risky thing and to treat the result as material.

If you’re an artist: make a piece and purposely do one thing you wouldn’t normally do — a color you avoid, an ugly line, an off-center composition. Then, instead of erasing it, ask how that choice changes the piece.

If you’re a writer: write a paragraph that sounds nothing like you’ve written before. Then revise it once using the three-step plan.

If you’re trying something social: say hi to someone you don’t usually talk to, and if it goes weird, note what you learned.

Keep it small. Keep it safe. But make the mistake on purpose and then use it.

If you want to, tell me about it. I love hearing those stories. They make my day.

I want to leave you with a line we say in the art studio: Original things are made from other things — accidents, glue, bad ideas and slow edits. Life is no different. You won’t get a perfect draft the first time. That’s not a flaw — that’s the process.

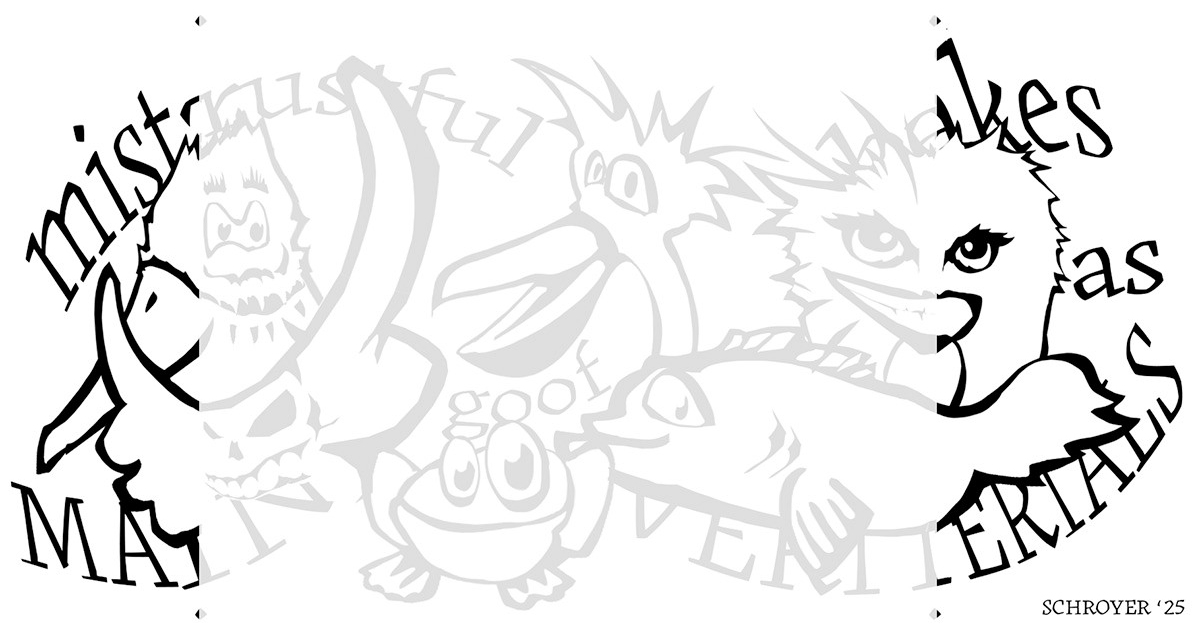

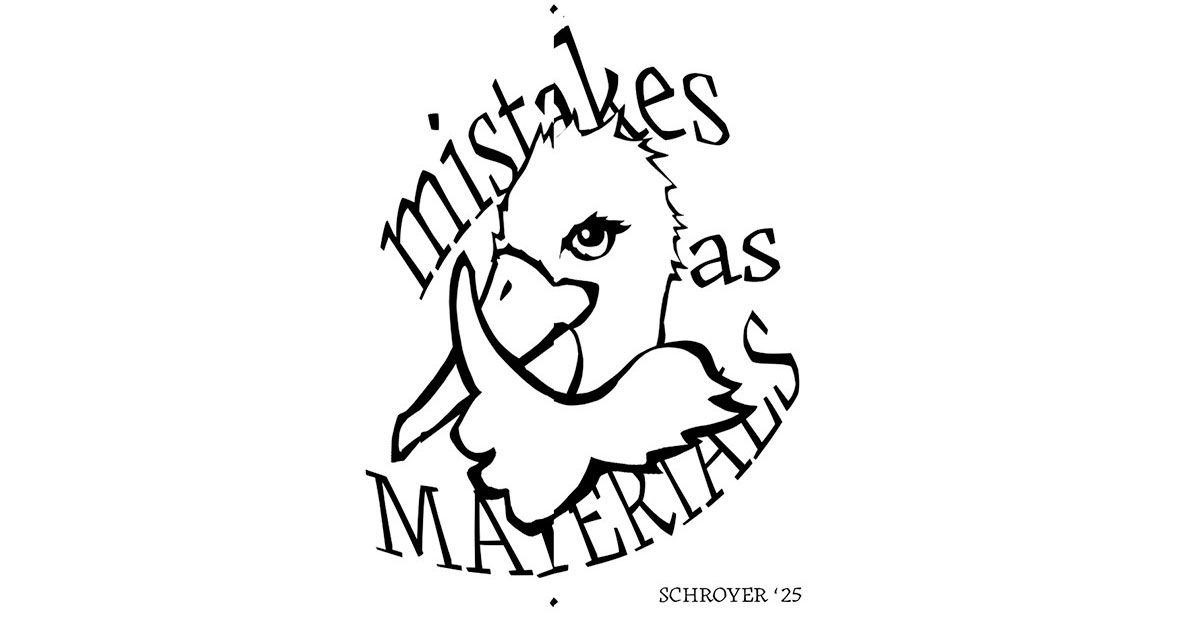

So next time something goes wrong, don’t apologize to yourself. Don’t try to pretend it didn’t happen. Put it on the table. Look at it. Name what it taught you. Try one small change. And then see what else appears. Look at this illustration on your chapel program (see below). This wonky, awkward, clumsy drawing that has some interesting things going on but clearly needs some help. See the two dots on the top, and how they line up with two dots on the bottom? If you take your program and fold it like this on one side…. And like this on the other side… and then bring those two parts together… It turns out there’s a whole other illustration here, we just needed to look at it differently.

So please, go make mistakes. Make your work. And use every single one of those mistakes as materials.

Thank you.