Deeds Well Done

John Franklin Enders of the Form of 1915 excelled in the humanities at St. Paul’s School. He went on to become one of the 20th century’s foremost scientists — and the School’s only Nobel laureate.

BY KRISTIN DUISBERG

Earlier this year, as COVID-19 and monkeypox vied for headlines across the United States, another infectious disease slipped back into the news: poliomyelitis, better known as polio, which began turning up in wastewater samples in New York City — decades after being declared effectively vanquished.

For most, polio conjures a few specific images, in the stark black and white style of a LIFE magazine photo essay: children in iron lungs, their smiles wide despite the metal chambers that encase their bodies; U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt, projecting a vigor that belies his wheelchair and the braces on his legs. But for those who knew him, polio calls to mind a different man entirely, soft-spoken and stoop-shouldered, toiling away over test tubes in a modest laboratory at Harvard Medical School.

John Enders, a member of the St. Paul’s School Form of 1915, didn’t contract polio, nor is his name immediately tied to the vaccines developed in the mid-20th century that led to the near-eradication of the illness across the globe. But those vaccines — the inactivated polio vaccine developed by Jonas Salk in 1955 and the oral polio vaccine developed by Albert Sabin five years later — were critically dependent on a discovery that Enders made in his Harvard lab in the late 1940s, as were many vaccines that followed it. The SPS alumnus developed a cell culture technique that made it possible to grow polio virus in abundance, in a test tube. Indeed, the discovery by Enders ushered in what many in infectious disease describe as a “golden age” of vaccines, and it earned him the 1954 Nobel Prize in Medicine that today is housed in the place where Enders began to chart his course for a life of intellectual discovery, the grounds of St. Paul’s School.

A WAY OF LIFE

Enders didn’t set out to be a Nobel Prize-winning scientist. In fact, he didn’t set out to be a scientist at all. Born in Hartford, Connecticut, in 1897, John Franklin Enders was the eldest of four children in a prominent family with only peripheral ties to medicine — he had an uncle who was a physician — but extensive ties to the business world. His grandfather, Thomas O. Enders, was a Hartford banker who later established the Aetna Life Insurance Company; in the late 1920s, his father, John Ostrom Enders, oversaw a series of banking mergers that created the Hartford National Bank and Trust Co. According to a biography of Enders published by the National Academy of Sciences, the bank’s clients included Samuel Clemens — the American humorist better known by his pen name, Mark Twain — “whose spotless white suits impressed the young [Enders] when the famous author visited.”

The first of his family to attend St. Paul’s (his brother Ostrom followed six years later), Enders was drawn to the humanities, studying Latin, French, German, and English literature and, according to his own account, struggling with math and sciences: “In mathematics and physics,” his National Academy of Sciences biography quotes him as saying, “I encountered difficulties which were surmounted in a most mediocre fashion only after great effort.” He was a member of the Missionary Society, played football and rowed with the first Shattuck boat, and as a Fifth Former wrote a poem that provided some early insight into his character, asking in part:

When I am old/And spindle shanks and sunken chaps/Betoken the coming of the fearful Last Event/What memories of youth will come to steel my heart/ Against the fear of meeting with my Creator?/Will then my heart be strong with thoughts of Deeds well done?

After St. Paul’s, Enders went to Yale to study English, leaving in 1917 to become a Navy pilot and returning after World War I to complete his degree. He graduated in 1920, and after a brief stint in real estate, headed back to academia with the intent of earning a Ph.D. in English literature and becoming a teacher. He’d completed his master’s at Harvard and was three years into a doctoral thesis on philology when one of his roommates, an instructor in Harvard’s department of bacteriology and immunology, introduced him to his department head, Hans Zinsser.

Out of sheer curiosity, Enders had begun to accompany his roommate to his laboratory in the evenings and, intrigued, started to question whether he was on the right academic path. Meeting Zinsser tipped the balance. Like Enders, Zinsser came from a humanities background, and had published poetry in The Atlantic Monthly. The bacteriologist’s capacity for standing simultaneously in the seemingly disparate realms of medicine and literature opened a whole new world of possibilities to Enders, who later wrote of his soon-to-be mentor, “Literature, politics, history, and science — all he discussed with spontaneity and without self-consciousness… . Voltaire seemed just around the corner, and Laurence Sterne upon the stair… . Under such influences, the laboratory became much more than a place just to work and teach; it became a way of life.”

Enders earned his Ph.D. in bacteriology under Zinsser in 1930 and spent the early years of his research career at Harvard studying bacteria. He expanded his study to include mammalian viruses in 1938 and, in 1941, partnered with half a dozen other researchers to study the viral illness mumps. Five years later, he was asked to establish a laboratory dedicated to infectious disease research at Children’s Medical Center in Boston, now Boston Children’s Hospital. It was there, working with research fellows Thomas Weller and Frederick Robbins, that he discovered and refined the laboratory cultivation technique for polio virus that made it possible for Jonas Salk to develop the first vaccine against the disease.

A CRITICAL BREAKTHROUGH

Today, it’s hard to fathom the significance of Enders’ achievement — on any number of levels. A highly contagious virus that attaches itself to cells in the intestinal tract and attacks the nervous system, in the late 1940s polio infected between 35,000 and 60,000 Americans every year, causing symptoms that ranged from fevers and neck pain to irreversible paralysis or death. The seriously ill ended up in iron lungs — mechanical respirators that supported the physical processes required for breathing — often for the rest of their lives. And while it had been more than 150 years since British scientist Edward Jenner had developed the first “modern” vaccine against smallpox, which he achieved by inoculating an 8-year-old boy with active cowpox virus, in 1949 no one had yet figured out how to grow the polio virus — or any virus — in a laboratory. Building off the 1931 work of Ernest Goodpasture, who had succeeded in growing pox viruses in the chorioallantoic membrane of embryonated eggs, Enders’ experiments represented a crucial step toward developing a vaccine against the disease.

“Growing viruses is complicated,” says Peter Wright ’60, an infectious diseases specialist at Dartmouth Hitchcock Medical Center who worked with Enders at the end of his career and has dedicated much of his own to researching vaccines for respiratory syncytial virus. “Viruses aren’t alive, so they require some sort of host, and the right media and conditions to allow them to replicate.”

Advances like the mRNA technology used to develop vaccines against COVID-19, Wright notes, make the ability to grow viruses less necessary today than it was 80 years ago, but the success of Enders in growing polio in a test tube using human tissue was groundbreaking — and a perhaps inevitable extension of his background in bacteriology. By using antibiotics, Wright explains, Enders was able to kill off other microbes that contaminated cell cultures and competed for nutrients, leaving the viruses to grow freely.

“That breakthrough allowed for the development of vaccines not just for polio, but also for measles, mumps, rubella, and chicken pox,” he says.

Also hard to fathom is the stance Enders took regarding the Nobel itself. Frederick Lovejoy ’55 was the chief resident at Boston Children’s Hospital and then a junior faculty member in pediatrics during Enders’ tenure. He says it was common knowledge that Enders initially refused to accept his Nobel Prize unless his two researchers, then early in their academic careers, shared in the award.

“When the Nobel committee called him from Sweden, he said, ‘thank you for the honor, but I’m not going to accept the prize unless my research fellows receive it, too,’” Lovejoy recalls. “They told him they didn’t think that was possible — that wasn’t how it worked — and he told them that he understood, and they could give it to someone else.’ And later they called him back and let him know they were going to award the Nobel Prize to him, Weller, and Robbins.”

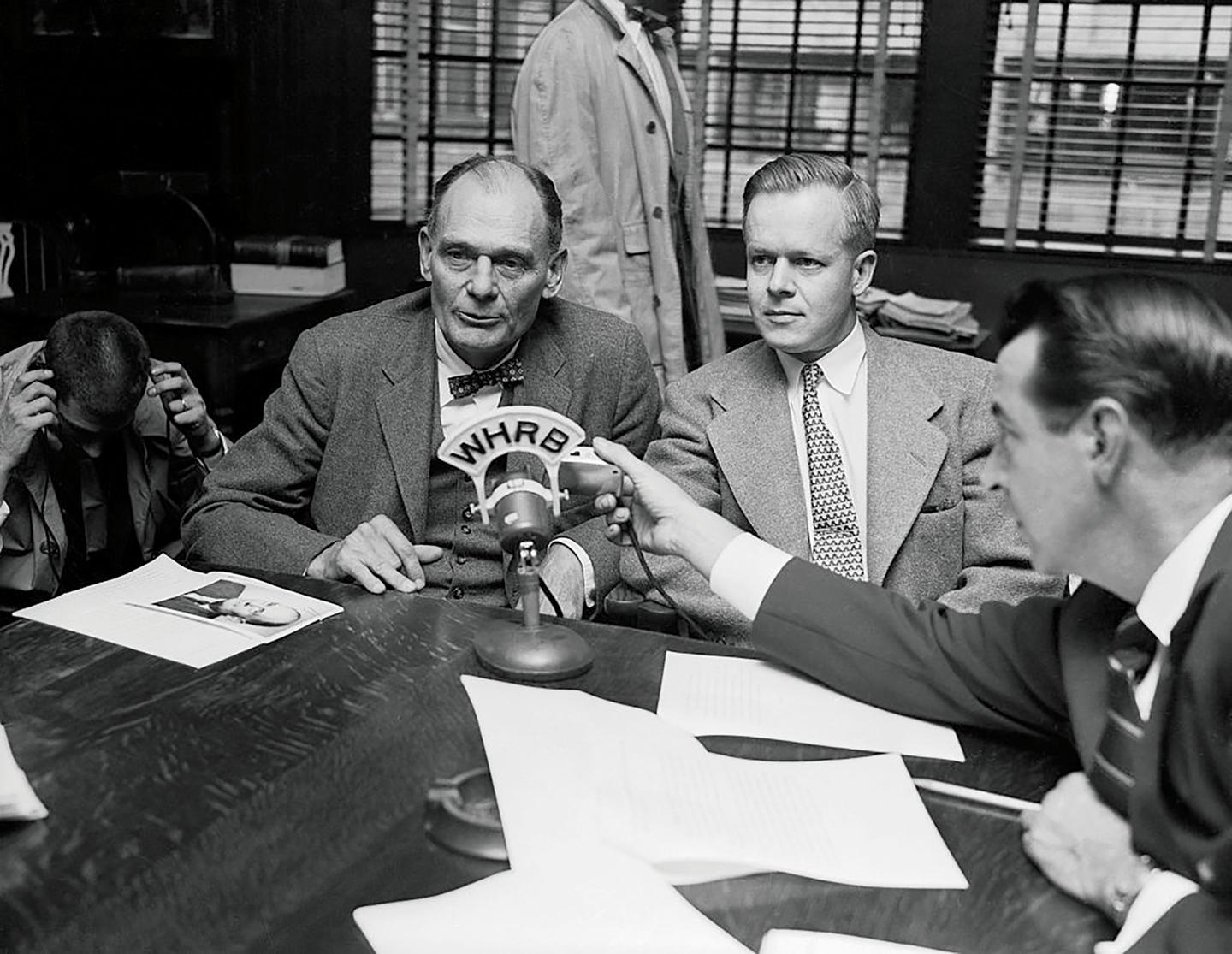

Enders receiving the Nobel Prize from the King of Sweden, Gustav VI Adolf, in Stockholm.

Both Lovejoy and Wright say this particular anecdote reflects the quintessence of the John Enders they knew: soft-spoken, unassuming, a man who carried his own lunch to work every day in a paper bag or a wicker basket and would call his lab members together in the afternoon to enjoy tea. Enders was in his seventies when Wright knew him, and he remembers him as still being very involved in the day-to-day work of his lab, and also quick to give a great deal of credit to others.

“We all knew about his Nobel, of course, and how important he was, but he did not act that way at all,” Wright says. “He was a very reserved person. It was very typical of him, I’d say, that he would ensure others got their due credit for their contributions to the work.”

Lovejoy describes Enders as a “central, central figure” at Boston Children’s, the namesake of the hospital’s 15-story John F. Enders Pediatric Research Laboratory, built in 1970, as well as the annual Enders Lecture, for which Lovejoy provides the introduction every year. For Lovejoy, there also is a personal dimension to his connection with Enders: his mother’s family was from Hartford, where the Enders family lived, and his mother was acquainted with John Enders growing up. It’s a connection that gives him a particular perspective on how remarkable — and fortuitous — it was that Enders pursued science instead of continuing in the family business as a banker.

“For him to go in such a different direction, as did one of his brother Ostrom’s sons, who later became a diplomat and an ambassador to Spain,” Lovejoy says, “… it’s remarkable what talented people choose to do, and the contributions they go on to make.”

EQUAL RECOGNITION

One hundred and twenty-five years after his birth and 37 years since his death, John Enders and his work remain relevant. “Every year, there’s a national infectious diseases conference called IDWeek, one of the centerpieces of which is the John Enders Lecture,” says Mehri McKellar ’87, an infectious diseases specialist at Duke University who was just starting her Fifth Form year at SPS when Enders died on Sept. 8, 1985, while reading T.S. Eliot aloud to his wife, Carol, and daughter, Sarah. “Dr. Enders is still a really big deal in the infectious diseases world. His work is widely regarded as the foundation of all modern vaccines.”

Today, the Enders name might not be synonymous with the polio vaccine the way Salk’s and Sabin’s are, or even with his 1961 success developing the first vaccine for measles, and certainly not with his late-life work to better understand the human immunodeficiency virus and the manner in which it leads to AIDS. But Enders himself seemed little concerned with his legacy, noting when Time named him one of its “men of the year” in 1961 that, “As a rule, the scientist takes off from the manifold observations of his predecessors,” and that it was simply the case that “the one who places the last stone and steps across the terra firma of accomplished discovery gets all the credit.” To that end, when The New York Times hailed Enders’ measles breakthrough as “one of the great achievements in medicine” that same year, he responded with a letter to the paper, insisting on recognition for six other scientists with whom he had worked.

For all his personal reserve, John Enders remains a tangible presence at SPS. His brother Ostrom graduated in 1921 and his son, John Ostrom Enders, was a member of the Form of 1946. Extended family members have attended the School through the decades, including one who graduated just this year. Enders himself was a driving force behind a fundraising initiative that allowed the School to make upgrades to the former Payson Science Building, and in 1986, his widow Carol Enders gave a gift to the School that included her late husband’s Nobel medal for display.

The first time Theresa Gerardo-Gettens saw the Enders’ Nobel Prize medal was in 1990, shortly after she joined the biology faculty at SPS. Today, the medal is mounted into a wall on the third floor of the Lindsay Center for Mathematics and Science — just around the corner from Gerardo-Gettens’ biology classroom. Gerardo- Gettens says she loves walking by the medal each day and often stops to read and ponder the words etched into the two glass panels on either side of the central display, which holds the medal and an image of Enders with the dates of his birth, death, and years at SPS. The right panel includes quotes from and about Enders; the left has the full copy of the poem Enders wrote in 1914, a Fifth Former already grappling with the question of whether he’d live a life of deeds well done.

“I was filled with awe when I first saw it and stunned that the Nobel had presumably been bequeathed to a high school,” Gerardo-Gettens says. “After reading the words written by a young John Enders, I began to think that St. Paul’s was no ordinary place.”

On one hand, it’s easy to imagine that the unassuming Enders might object to the considerable size of the display, some 10 feet wide by 8 feet high. On the other hand, as a man who cared more about recognizing the work of others than accepting praise for himself, he might appreciate that on a sunny fall afternoon, the black glass triptych that celebrates his achievements also reflects passersby — students with laden backpacks and smiling faces, on their way to biology or chemistry classes or maybe the state-of-the art laboratory that contains one of the country’s only high school-based quantitative polymerase chain reaction machines, perhaps taking their own first steps toward an extraordinary scientific discovery for the benefit of the greater good.

Nia Goodloe-Pierre ’23 and Science Teacher Sarah Boylan, director of the Advanced Science and Engineering Program (ASEP), in front of the Lindsay Center display that holds John Enders’ Nobel Prize medal. During the summer of 2022, Goodloe-Pierre completed an ASEP internsip at City College of New York, where she studied the interactions between antibiotic-resistant bacteria and host cells, genes associated with the cholera toxin, and competitive fitness of V. cholera.

Nia Goodloe-Pierre ’23 and Boylan working in a nearby LIndsay Center lab.