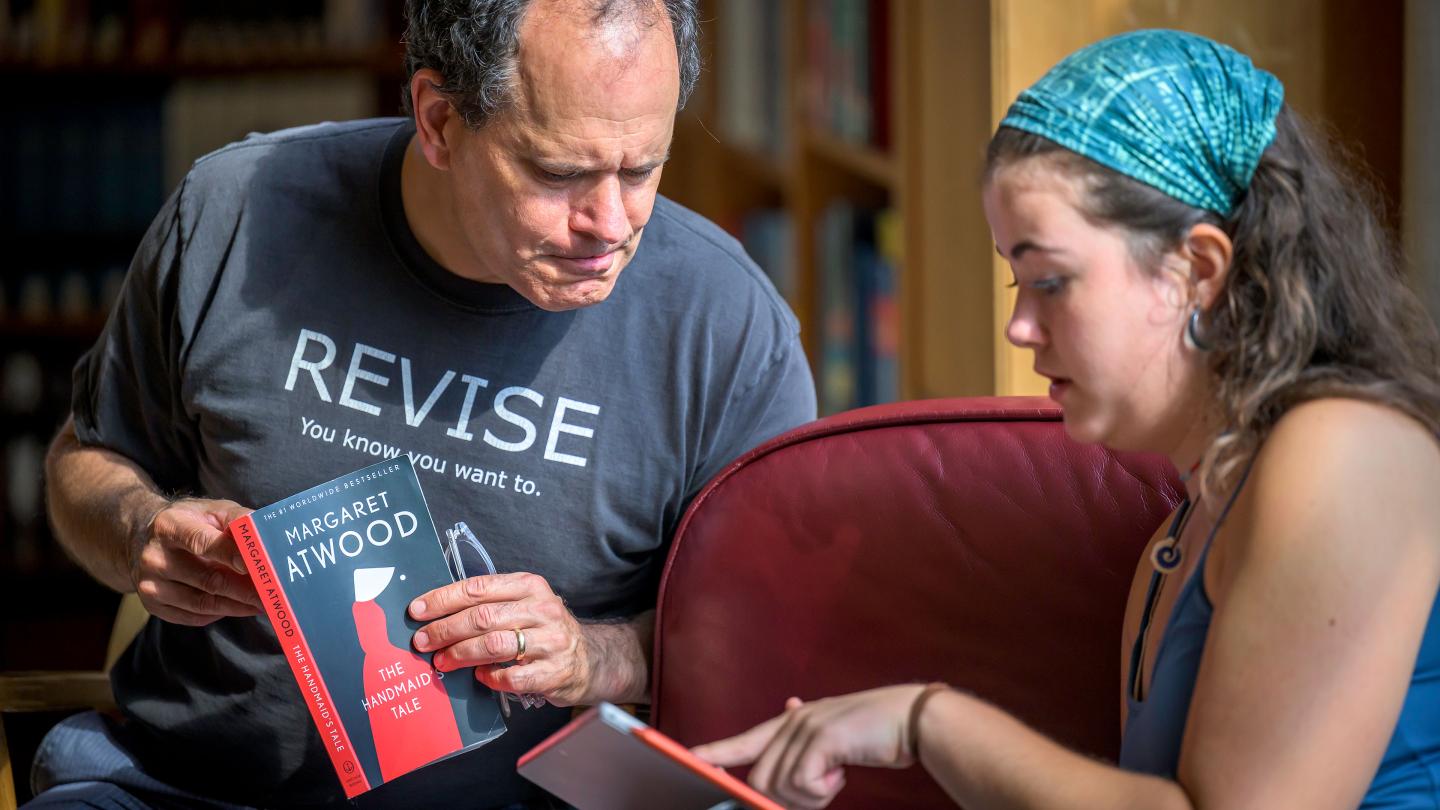

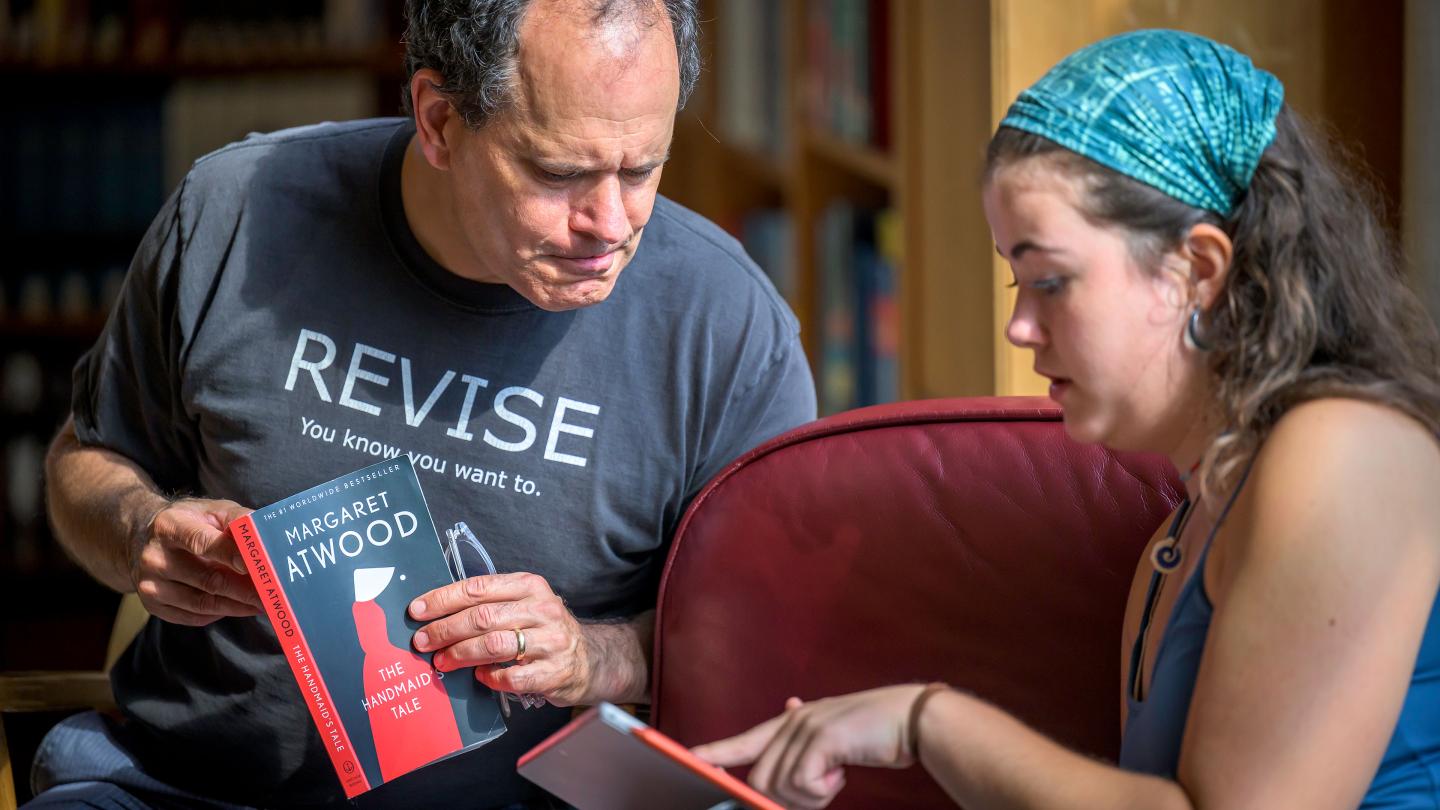

Chris Canfield’s ASP class provides an important outlet for understanding challenged texts.

BY JANA F. BROWN

In his discussion-based Forbidden Fictions class at the Advanced Studies Program, teacher Chris Canfield says there’s one topic that consistently entered the daily conversations of his 12 students.

“We probably read six articles about the current situation with people challenging books,” says Canfield, who teaches English at Moultonborough Academy in New Hampshire and is in his 11th year at ASP, “and one of the things my students [kept] asking is, ‘Did these people actually read the books?’”

Class members often returned to the idea of context, and understanding the full picture when discussing why the content of certain books has been challenged. Canfield notes that “banned” often means the offending texts have been removed from library bookshelves, but not necessarily from the curriculum.

In the nearly six weeks that Canfield spends with his ASP students each summer, the goal is to encourage them to consider the various perspectives involved in book banning, who makes the decisions and why those decisions are made. The reading list for Forbidden Fictions gives students a chance to examine the type of content that elicits criticism, including texts that address issues of racism, sexuality, abuse, religion, profanity and political conflict. In addition to articles on the subject, the students have read “The Absolutely True Diary of a Part-Time Indian” by Sherman Alexie; “Slaughterhouse-5” by Kurt Vonnegut; “Persepolis: The Story of a Childhood” by Marjane Satrapi; “Reading Lolita in Tehran: A Memoir in Books” by Azar Nafisi; “Beloved” by Toni Morrison; and “The Handmaid’s Tale” by Margaret Atwood.

They also have analyzed collections of poetry, including “Whereas” by Layli Long Soldier. This year, for a final research project, students were asked to choose from one of 10 challenged books. Hopkinton High School’s Elizabeth Trafton elected to read “Out of Darkness” by Ashley Hope Pérez. Set in Texas in 1937, the novel tells the story of a romance between a Mexican-American girl and an African-American boy. Trafton began her reading with the knowledge that the book had been challenged for its depiction of graphic sexual content, including abuse, but was surprised to discover that the scenes were not unusual for what a typical high school student might read. It helped to reinforce the conclusion she and her classmates reached during their summer experiences.

“The book covers difficult topics,” Trafton says. The author hypothesizes that it was for these reasons that the book was often banned. I was surprised to discover that the quote most often used to ban the book, when put into the context of the story, does not promote the same misogynistic ideology it is often twisted to portray. This made me consider the possibility of whether many of the books that are challenged or banned in schools are done so purely because the people banning them haven’t read the whole story.”

Canfield considers the memoir “Reading Lolita in Tehran” to be the class’s main critical source, a jumping off point for students to consider what it’s like to live in a country where book banning can serve as a prelude to more expansive censorship, including shuttering the doors of universities.

Two years ago, Canfield wondered if Forbidden Fictions had run its course. The class had not been popular enough to offer in 2021, “but then, all of a sudden, it’s become this huge issue again, these challenges to texts.”

In addition to their intensive reading schedule, Forbidden Fictions students also explore themes and form their own questions in preparation for class discussions. It’s all designed to hone their critical thinking skills and teach them how to closely examine the authors’ choice of words — and what life experiences might trigger a desire for those words to be banned.

“It has made me challenge my own ideas because I believe students should have access to multiple perspectives,” Trafton says. “As we talked about in one class discussion, what if the information in a book is misleading? And how do you determine what could be traumatizing for young children? The class made me consider all perspectives, and gave me a lot more information to form my own opinions in a much more educated way.”