Hanzhong “Tim” Mei ’21 and others find their voices through the BIPOC student art show

As a self-proclaimed critical thinker from a young age, Hanzhong “Tim” Mei ’21 arrived in the United States from Shanghai, China, seeking a challenge. He enrolled as a seventh grader at Rumsey Hall School, a junior boarding school in Connecticut. And, while he found the academics met his expectations, he admits he struggled to fit in.

In addition to managing a language barrier, Mei was frequently answering questions born from American stereotypes about life in China. Did he eat dogs? Was he a communist? In order to make friends, Mei used self-deprecating humor.

“Part of my identity was slowly being undermined,” says Mei, 18. “In middle school, I stepped toward a regrettable path. I started making fun of myself and my identity. I attempted to trade away my pride for some brief moments of popularity. That persisted and, by the end of middle school, I was struggling with my identity. I felt ashamed that I was Asian, and it got to a point where I didn’t even want to speak Chinese.”

Though there are times when he still struggles against conformity, Mei has felt more comfortable in his own skin during his three years at St. Paul’s. In a Chapel speech last month, he spoke about the support he has received from his peers in the Justice and Social Equity for Asians (JSEA) group, including the opportunity to attend the Asian American Footstep Conference, which brings together high school students of Asian descent. He is also a Classical Honors Scholar, who has bonded with fellow members of the Classics Society, and serves as art editor of Horae Scholasticae.

In addressing the SPS community, Mei also shared his understanding of the concept of “eating bitterness” – treating suffering as a virtue. While he admits that he has had moments of regret for remaining silent in the face of insensitive comments at St. Paul’s, he has found his voice – and identity – through the arts.

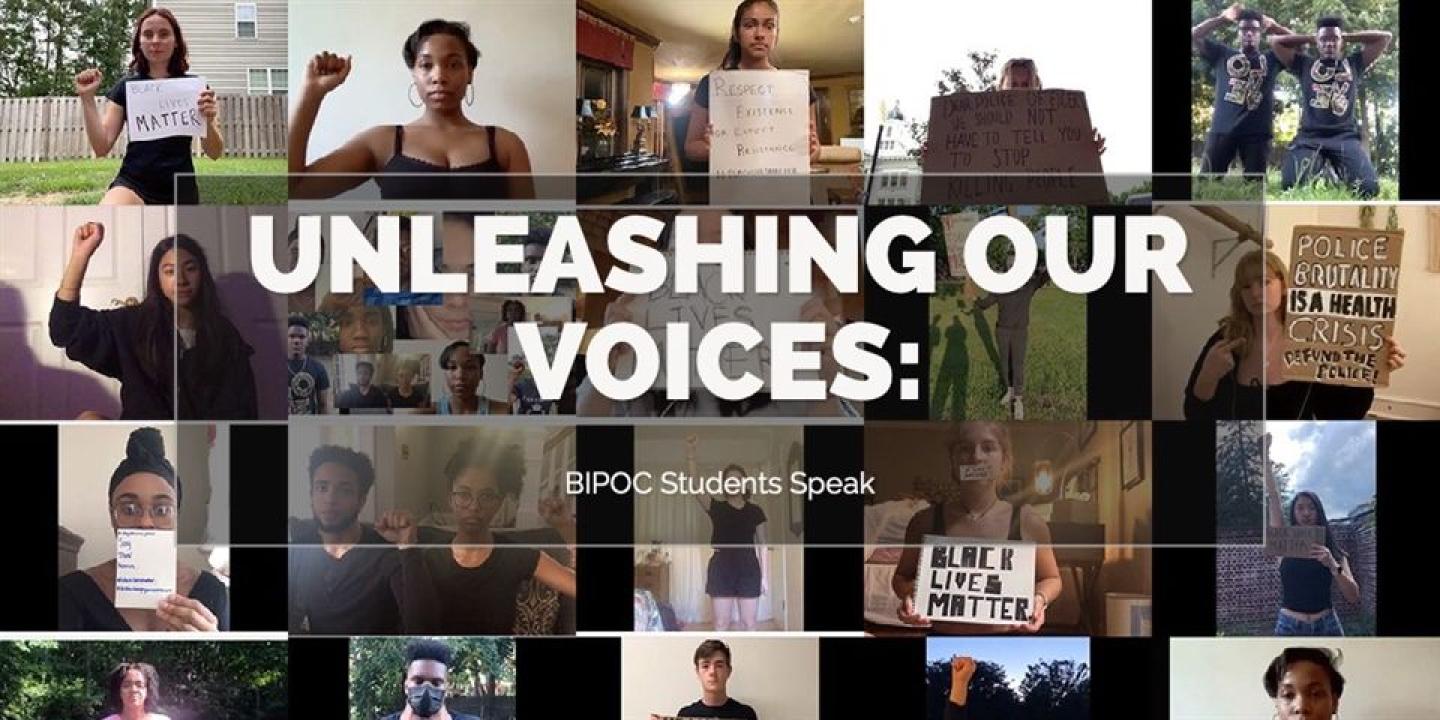

At the start of May, in conjunction with Asian American and Pacific Islander Heritage Month (AAPI), St. Paul’s opened the student art exhibit Unleashing Our Voices at the Crumpacker Gallery. The BIPOC art show, first proposed by Mei, features the work of 11 SPS students, including eight pieces of photography by Mei. The 33 student creations on display range from prints to poetry to digital drawings to documentary film.

“It’s great to celebrate Asian culture [through AAPI Month],” says Mei, “but to celebrate also means to care about our stories and listen to our struggles.”

During time away from St. Paul’s at the height of the COVID-19 pandemic, Mei worked independently to create his provocative photographs, with guidance from fine arts faculty member Leigh Kaulbach ’08. He credits her, along with Crumpacker Gallery Director Colin Callahan, the Rev. Charles Wynder, Jr., SPS dean of cchapel and spiritual life, and JSEA advisers Deb Vo and Jenny Li for facilitating and championing the exhibit.

“The intention of the show is to raise awareness of more BIPOC student experiences,” explains Mei. “The past year has been a lot for all of us. We want the rest of the community to know how we feel. As artists, we wanted to let other people know art is a strong way to advocate for what you believe in.”

Mei’s own work, he says, was inspired by the self-portraits of artist Cindy Sherman, whose first photographic sequence challenged society’s attitudes toward gender roles. Through his self-portrait series, Mei intends to reflect American stereotypes of Asian people. Kaulbach praises him for creating a “compelling body of work” that uses “classic composition to address social justice issues.” Among the featured images are Silenced, in which Mei covered his mouth with masking tape while attempting to speak, and Invisibility, which features a headless Mei dressed in yellow clothing, merged into a yellow background. He shared in Chapel that the images are exaggerated to cause discomfort for the viewer.

“If you find yourself uncomfortable,” Mei told the SPS community, “I urge you to take the extra second and ask, ‘Why?’”

Invisibility, adds Mei, is a symbol of the lack of empathy for the societal biases faced by Asians, particularly in America. Asians, Mei says, are portrayed as living the “model minority life” and are therefore not always seen. This idea has been escalated during the COVID-19 pandemic and concurrent rise in anti-Asian hate crimes. In the early days of the pandemic, Mei was stuck in New York City, unable to get a flight home to Shanghai. He worried about being targeted simply for his ethnicity as violent incidents increased.

“Artistically speaking,” explains Mei, “I went through several editions [of Invisibility]. In one, I was covering my face. I purposely hid my head and only showed my back to incorporate the [perception] that all Asian people look the same.”

Response to the show, which was on display through the end of May, has included words of encouragement from peers and faculty for Mei and the other student artists. According to Associate Dean of Admission Michelle Hung, faculty adviser to the SPS Women of Color group, Mei’s Chapel speech and artwork have “helped raise visibility and added to the discourse about Asian and Asian American students in a way that other students can understand.”

Mei has felt supported in his efforts to bring awareness to the perspectives of BIPOC students through Unleashing Our Voices and is gratified by the use of art as a medium for activism. He expects to continue using his voice when he begins his undergraduate studies at the University of Chicago in the fall.

“I wanted to tell people it’s okay to go through these things,” says Mei. “What’s more important is coming out of it and gaining a better understanding of yourself and helping others.”